For a deeper sense of self, meaningful relationships and a psychologically healthy and soulful spirituality.

-

Visit Our Place

91-6 Čaka Street, Riga

-

Tr. - Ce. 9:00 - 18:00

- Request a visit

I have noticed that many people are internally tense about the same subject - their [in]normality. In my experience of psychological counselling, I have noticed that there are a number of clients who, after presenting their problem, expect the psychologist to reassure them that they are not abnormal, that it is normal to experience what they are experiencing (which, for the most part, it is).

So let's talk about what "normal", "being normal" and "conforming to the norm" really mean.

What is the norm - from a statistical point of view

To understand what is really meant by "norm" and "normal", let us first take a statistical perspective, which in our society is the main yardstick by which the conformity of human beings and anything else (weather, traffic flow, etc.) to the norm is measured.

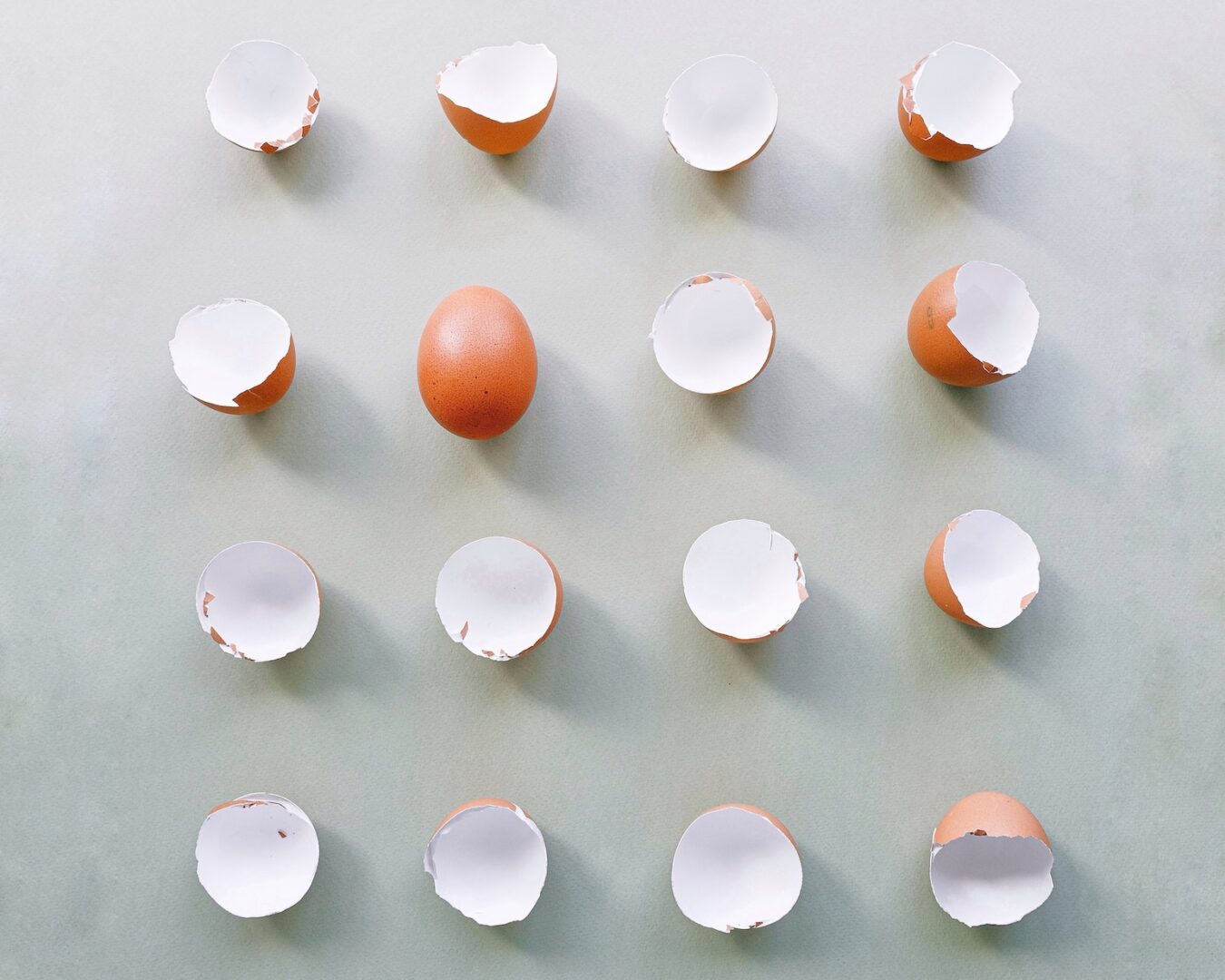

Statistically, the concept of normality is based on the idea that normal is what is most common. It is a mathematical calculation that provides information about which measurable items in a range of items (e.g. different expressions of human behaviour) are more common in a given set of people. Accordingly, those items that are counted as occurring most frequently are considered to be within the norm ('normal'), while those items that occur less frequently are considered to be outside the norm (abnormal, abnormal, pathological or, in the vernacular, 'abnormal').

A perfect normal distribution curve has a bell shape, which is rare in nature). What does this mean? An easy to understand and therefore often used example to understand the concept of normal distribution is the story of people with different heights. If we were to measure the height of all the people in the world, we would get a bell-shaped curve with short people at one end (a relatively small proportion), medium people in the middle (the majority of the population) and tall people at the other end (also a relatively small proportion). The average height of a person is taken as the arithmetic mean (mean - which, by the way, is just a mathematical average, not the most common unit (fashion)). People whose height "swings around the average" to one side or the other would be of normal height, while everyone else would be more or less outside the norm.

So, the first important thing to understand is that, statistically, mathematically, anything that shows consistency with the majority, that is, +/- consistency with the arithmetic mean, is considered the norm.

The second important thing to understand is that every normal division has two ends. Another simple example. If we look at the performance of pupils, those who are mediocre will fall within the range that is defined as the norm. On the other hand, outside the norm there will be both underachievers and achievers.

The third key point. Everything is a spectrum. For any size (height, performance, personality trait, mental disorder) there is a gradation: from short stature to tall; from poor performance to excellent; from a weak character trait to a strong character trait; from minimal symptoms to strong symptoms.

The fourth key point. Whatever the measurement, there will be individuals (events, objects, etc.) in any process, behaviour, action or characteristic that are statistically outside the normal range or "abnormal". This is normal. It is mathematics.

What is normal - from a biological (medical) point of view

If we look at it from the point of view of biological processes, then human normality, normal physical functioning, is determined by biological processes themselves. Those biological processes that fall in the middle of the normality curve (the most common) define what health is, including mental health. On the other hand, those processes that are outside the normal range are considered abnormal and signal the likelihood of disease.

However, there is a problem with applying this criterion. People would of course like to think that we have studied everything and fully understand human biological functioning, but this is not even close to the truth. The scientific understanding of human biological functioning is still incomplete. History shows that various biological processes are often misinterpreted as pathological. Examples include the historical view of homosexuality, the experience of transcendent states of consciousness, etc.

What is the norm - from a social and cultural perspective

From a social and cultural perspective, normality is what most people consider to be acceptable, moral, ethical, appropriate behaviour, self-expression, etc. Culturally defined norms are subjective, a collective agreement on the same rules. The majority opinion is considered the norm. Moreover, this understanding of the norm is often influenced by history, by the various events and processes that society is confronted with. Different social environments and cultures have different understandings of what is "normal" and what is not. This is only a subjective interpretation at a collective level.

What exactly is the norm?

To sum up, "abnormal" does not always mean the same thing as "abnormal". Most often it means "out of line with the majority of a particular group of people", nothing else.

The word "normal" is NOT antonymous with "abnormal" (meaning "crazy", "deranged", "physically or mentally ill", or in any other way "disordered"). The antonyms for "normal" are "abnormal", "abnormal" and "abnormal". Of these, 'abnormal' means 'rare', 'abnormal' means 'having a significant deviation from the average' and 'abnormal' is understood as 'associated with physical or mental illness'.

When is being out of the norm perceived as "normal"?

If we look at the concept of the norm from a psychological perspective, there are many cases where it is being outside the norm, rather than fitting in, that is perceived as "good" and "positive". For example, it is being outside the norm that shapes our personality traits. Something that is specific to us, something that defines our individuality.

For a better understanding, I'll use the Latvian Personality Survey (Perepjolkina, 2013) interpretation of the results. When a person completes the test (with the aim of finding out which personality traits they have), the results are processed and interpreted by comparing that person's answers with the majority mathematical data. It is precisely those traits in which a person shows himself to be outside the norm ('abnormal') that distinguish him from others. Thus, in this context, it is precisely being out of the norm that defines the uniqueness, the specificity of a person's personality, that distinguishes him from the majority.

Gaining and losing at the same time

Looking at these personality trait scales in the example above, not only does it show that "everything is a spectrum", but also another nuance. That every tree has two ends. That is to say, if we are at one end of the spectrum, we cannot be at the other. For example, we cannot be both introverts and extroverts at the same time. So, wherever we are and whatever personality trait we have, we are both relatively gaining and losing at the same time. As we gain extraversion (sociability, gregariousness, joie de vivre, adventurism), we lose introversion (emotional reserve, reticence in communication, tendency to self-reflection) and vice versa. We cannot be at both poles at the same time. We can be more extroverted in one situation and more introverted in another.

From this prism, I would like to stress that sometimes, somehow, a relative loss is a kind of price we pay for what we gain For our difference, which sometimes hangs only on our inherent talents and abilities. For our uniqueness.

As a striking example, I would like to mention something that is considered pathological in our latitudes, and therefore definitely outside the norm. For example, schizotypal personality traits, schizotypal disorders and schizophrenia are placed in the pathology basket from a medical point of view. However, there are studies showing that people who have these pathologies or abnormalities are more creative and artistic (Acar, Chen, Cayirdag, 2018; Vellante et al., 2018), so - talent. Moreover, it is also a paradox that the bizarre beliefs, experiences and perceptions that are characteristic of schizotypy, and which are considered pathological, are at the same time associated with a person's mental health (Lifshitz et al., 2019; McCreery & Claridge, 2002). The following version of this paradox has been proposed. How we subjectively interpret when we experience something supernatural is related to what happens to our mental health (Goulding, 2005). So, if we translate experiencing something supernatural, magical, strange, weird, funny as something good and positive for ourselves, our mental health only benefits. Conversely, if we translate it as something negative, our mental health loses.

Understanding the norm is changing

Another important nuance is that the understanding of the norm is changing, and changing constantly. What was normal a long time ago is no longer normal today, and what is normal today will not be normal in time. It is normal, and this can apply to social and cultural norms, to biological norms, and to personal norms that we subjectively invent for ourselves.

Some illustrative examples of the view:

- In Latvia, peasants were "given" surnames only at the beginning of the 19th century;

- Women only gained the right to vote in the early 20th century;

- Homosexuality was only removed from the DSM in 1973;

- 10 years ago, restaurants didn't have vegetarian menus and you couldn't buy products with the eco-label at Rimi;

- Before 2020, it was not normal to walk down the street wearing a face mask in most countries.

Being outside the norm defines who we are

What am I trying to say? If there is one thing I have really understood during 5 years of studying psychology, it is that there is no such thing as "normal" or "abnormal". It is just the way it is. It is being outside the norm that creates in us those uniquenesses and peculiarities that make us individual and different from each other (I cannot stress this more!!!).

What is normal and normal is defined by people themselves, by society. So any norm can also be redefined by people, by society. This happens all the time. It is only normal to change norms and to reflect on what is normal and what is not.

Why is it important for me to write this, to tell others

Quite simply, I myself have long been one of those people who question their own normality, and it was understanding the concept of normality that finally freed me from my inner tension and strain. This understanding gave me the emotional permission not to conform to the norm and to realise that that was okay. It also freed me from the urge to be normal. Perhaps by sharing my insight with someone else, I can use it to help unlock similar feelings.

I am not the norm in many areas, I have noticed that for a long time. I am f***ing strange. It is and always has been. For example, I have always wondered about the answers given by the majority when reading the results of social surveys and thought "who would even think that!?". Yes, on the one hand it makes it difficult for me to fit in, to socialise, which makes my life quite lonely. But on the other hand, it gives me the ability to think differently, to see differently from the majority and to come up with original ideas and solutions.

Through understanding the concept of the norm, I realised that the problem was not my weirdness, but the idea that society cultivates that you have to conform to the norm. Not fitting into the norm is perceived as a bad thing, when this perception is mostly based on a lack of understanding of the words we use. And often without thinking about the consequences of those words.

Ideas we cultivate

It is interesting that at the same time, the idea that a person must excel in some area of life, must achieve success, is also cultivated in society. Why is that interesting? Because excellence is not the norm. To get into excellence, meaning - to surpass the majority - is to get out of the norm. It is mathematically impossible to be excellent and to be in the norm at the same time. Any person who excels in any field, whether a professional athlete, a world-famous musician, a fashion designer, a writer, an electrical engineer, a fitness trainer, a politician or anything else, does not fit into the norm. He doesn't fit in with the majority, and that's what makes him great. That is what makes him different and bright in the eyes of the majority.

All the benchmarks we aspire to are not the norm. For example: a beautiful beach body; beautiful, pearly white teeth; that perfect yoga pose you want to stand in so badly; the ability to manage your time perfectly; singing in a voice as pure as an angel's; a morning routine that is perfectly integrated; a family where everyone understands each other halfway; a daily life spent feeling fulfilled, grateful and loved... If that were normal, most people would already fit it, would already be there. Look, whatever you want, the public is promoting the image of the "abnormal" person and at the same time demanding normality.

Personally, I wonder, if we all (I really believe we all) strive to be authentic, to be ourselves, unique, expressing and developing talents and abilities that only we have (this idea is also cultivated in society), then why are we so concerned about this question "am I normal"?

Why do we even care if normality, by its very meaning and essence, contradicts the idea of human beings as unique creatures? Being normal or conforming to the norm and expressing one's individuality are two different things. It is incompatible to be mediocre and unique at the same time.

Yes, of course, there is the other side of the coin - the other end of the normal distribution curve. Something that we certainly do not aspire to, something that we would like to see as non-existent. Something we would love to turn off and forget altogether. It's where we don't want to get to and where getting to is bad. On the other side of the curve are the "bad", the "black", the "sick", the "weak", the "incapable" who should be "normalised", "cured", "rescued from the pit". It does not matter whether we are talking about people, objects, events or anything else.

Interestingly, this side of the normality curve is definitely not what we think of as the norm, unlike excellence, which is exactly the same as one end of the normality curve, and which we mistakenly tend to translate as something "normal".

For me, it is never a question of how to make or remake oneself or other "bad" people normal, but how to live with what exists in oneself and in others in the best possible quality. It is about how to play the cards we have been dealt to our advantage, to gain a resource. If we stop being victims of the situation, we can get resources from everything we experience.

A call to be "abnormal"

If you only knew how much I long for a society that is less "normal". After redefining norms (again, and again, and again). For going wide and deep. For space and breath for "abnormality". For authenticity. For naturalness. For uniqueness. For individuality.

Yes, I know, no one will bring about the "insanity" I want but me. People follow other people's example, so the only way to change the existing norms is to start expressing your "insanity". The more people are outside the norm, the more the perception of the norm will change. Want to change the world? Change the norm! Change your thinking, your behaviour, your actions! Be unique, authentic, individual! Be "abnormal!"

Normality is mediocrity. To be normal is to be typical, grey, someone who does not stand out from the majority. "Abnormality" is the price we pay for being different. All our imperfections and differences make us perfect. All our "abnormalities" make up our uniqueness. They make us who we are.

This free content is produced in my spare time without pay. If you see value in what I do, I'd be happy to make you a coffee! It's like a spur to create new content! 🙂

Sources:

Acar, S., Chen, X., Cayirdag, N. (2018). Schizophrenia and creativity: A meta-analytic review, Schizophrenia Research, 195, 23-31.

Goulding, A., (2005). Healthy schizotypy in a population of paranormal believers and experiencers, Personality and Individual Differences, 38(5),1069-1083.

Lifshitza, M., van Elkc, M., & uhrmann, T. M. (2019). Absorption and spiritual experience: A review of evidence and potential mechanisms, Consciousness and Cognition, 73, 102760.

McCreery, C. & Claridge, G. (2002). Healthy schizotypy: The case of out-of-the-body experiences. Personality and Individual Differences, 32(1), 141-154.

Perepjolkina, V., Reņģe, V. (2013). Latvian Personality Survey (LPA-v3). Test manual, Latvia University.

Vellante, F., Sarchione, F., Ebisch, S.J.H., Salone, A., Orsolini, L, Marini, S., Valchera, A., Fornaro, M., Carano, A., Iasevoli, F., Martinotti, G, De Berardis, D., Di Giannantonio, M. (2018). Creativity and psychiatric illness: A functional perspective beyond chaos, Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry, 80, 91-100.

Tags :

Sense of "I"Identity

Search

Topics

Recent publications

- Insights from EBIT: the growth of organisations starts with the psychological well-being of people

- Why workplace spirituality is the key to organisational flourishing

- How to find the meaning of life?

- Common misconceptions about what contributes to a sense of meaning in life

- Why is a clear identity and sense of self a prerequisite for a psychologically healthy spirituality?

The content of this website may only be quoted, reproduced, republished and otherwise distributed in accordance with applicable copyright laws. For commercial use of the content, please contact and obtain permission.